The Most Beautiful Names

or what do you worship?

You know what it’s like when you get a sliver in your finger, or maybe in the sole of your foot? If it’s driven in so deep that there’s nothing a tweezer can get a grip on, it can just stay there for a long time, not bothering you until something accidentally presses against it.

That’s what religion has been in my life. A thorn that just won’t budge.

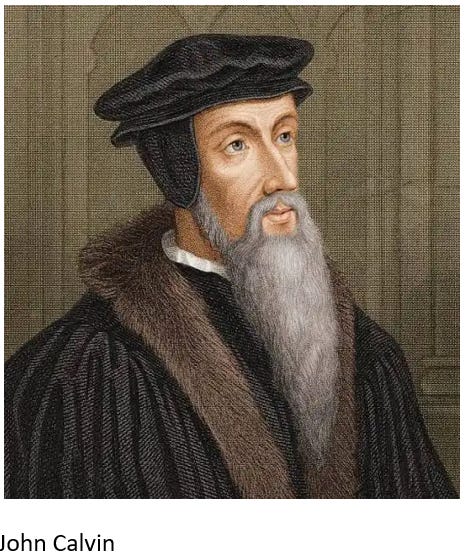

I was raised a Calvinist. That won’t mean much to younger generations. John Calvin pretty much invented the Protestantism that served as the origin for most of the Christian denominations that now exist around the world. If you’re not Catholic, you’re probably sitting in the pews of a Calvin-inspired church. Or more likely, you sat in them occasionally as a child, but haven’t visited in years.

I lost my faith, as they say, in my early twenties. Then I was stuck with nihilism, which is not a pretty place for a young person. Life is meaningless and empty? How am I supposed to get up in the morning? I imagined myself as one cow in a field of cows, just hanging out purposelessly, chewing the cud. At least it stopped me from pulling out the kitchen knives.

Thankfully I discovered other religions, and began my pretty much life-long investigation into them. I checked out Buddhism, spent years chasing yogis and gurus on their spiritual paths, took a trip into Sufism.

It was in the teachings of Sufism that I discovered the most beautiful names of god.

The Sufis, the mystics of Islam, say the world was created from the ninety-nine most beautiful names of God. Ninety-nine is just a number that symbolizes many, and “names” means attributes or qualities. They speak, for example, of “God the merciful”, in which the characteristic, “merciful,” is one of the names of God. If the entire universe – including but not limited to humans -- is formed of divine attributes, everything is made up of unique combinations of an assortment of these attributes. In this way the divine exists within the atom and is the gene within the gene. Our genetic heritage stretches beyond matter.

All the divine attributes, they say, can be divided into two almost limitless categories: the categories of beauty and of majesty. The category of beauty contains attributes that attract us, that give us a desire for closeness with the divine (or any of its multiple manifestations), and the category of majesty contains attributes that we need to be cautious about, that keep us at an appropriate distance.

Those that give us a sense of closeness include names like God the beautiful, the tender, the gentle, the loving, the merciful. Those that keep us at a respectful distance include things like God the strong, the wrathful, the judgmental, the violent. For Sufis the divine invites people to intimacy with itself, while at the same time reminding people of the importance of boundaries.

These are categories of movement, toward and away. In this they parallel all the movement of the universe. Everything alive moves toward and away, contracting and expanding. The tides come in to kiss the beaches and embrace the ocean cliffs, then withdraw to their deep and distant regions again. The ventricles of the heart close and open again to give us our pulsing veins and arteries. Subatomic waves crash into their particle-ness, which throw off their bonds to unleash their wave-ity again.

Think, for a minute, of babies being born, each with an individual, unique selection of divine attributes -- of desires for and barriers against. We have to learn to weave between for and against, desire and withdrawal, all the pushes and pulls of our jar full of beautiful names. We can’t find ways to harmonize our pull toward intimacy and our retreat into separation until we can harmonize those forces within our own selves.

Beauty and Majesty, intimacy and separation. The child grows in the womb, almost at one with the mother, then explodes out in defiant separation. From familial bonds, we mature into our own separate places, then create familial bonds again. Expand, contract.

In western cultures we divide the characteristics we call human – we don’t think of ourselves as divine in any way – similarly, but we call them “masculine” and “feminine”. They are static qualities. And they are oppositions. They are boxes symbolizing an idea and we then try to squash the real world – real males and females – into those boxes. We demand that males align themselves with the masculine, and females align themselves with the feminine.

If you’re biologically male, your caregivers, acting in the name of society, are going to squash all the qualities associated with closeness, beauty, intimacy out of you, and try to squeeze in the qualities of strength, fierceness, independence whether you have them in potential or not. And the reverse if you’re female. From a Sufi perspective, society tries to kill some of the divine in us as soon as possible.

But how can a being trapped in independence and autonomy even make an approach to an other? When all desire for closeness has been weeded out, how does he even know what he wants from an other? The best he can hope for is stimulation, something to make him feel alive in his aloneness and separation.

And how can someone with no sense of autonomy and independence and separation approach an other without dissolving her own boundaries and losing all sense of herself? The best she can hope for is never-ending romantic delusion of union.

The western way of dividing provides for no relations between the sexes except that of domination and submission.

And it’s almost impossible for people to be authentic.

It’s been too hard for women for too long, of course, and so there have been “women’s liberation” movements again and again. Women have only to find their god-given strength to start lobbying, maneuvering, fighting for the right to be accorded equal status, as human beings, with men.

Men, on the other hand, gain too much from their inauthenticity. Those who do not have the divine names of “strength” or “ferocity” or “leader” have to pretend to those qualities. That makes them brittle, and, frankly, dangerous in the way that men who have to prove themselves always are. In exchange, they get to set the rules of all the games, they get heard when women are not, they get to speak when women don’t get that privilege, they get higher pay, or they just get the job. A man who’s good at faking it can have a good life.

Too many women still fake it too, because no movement can liberate the individual from an internalized prison. Movements can only make change in the body politic, not necessarily in the psyche.

Some days I am beyond believing that whole societies, whole civilizations can prefer such fakery of their members to authenticity.

Can you even imagine a world in which men can commonly invite closeness by their natural warmth, empathy and willingness to listen? And a world in which women can effortlessly command attention and respect because their intelligence, charisma and problem-solving skills make them the obvious leaders?

The Sufis also say that we each worship a god of our own creation. Since god (if there is such a thing) isn’t out walking and visible to all, we have to conceptualize a God to worship. And we conceptualize based on what we’re familiar with. Mostly religious people conceptualize some version of their own fathers. If their own father was distant, cold, withholding of approval, quick to punish, well then that’s the God they worship.

I like a short passage from the biblical book of Hosea, in which the Jewish prophet has a vision of the divine speaking to him. The divine presence seems to say “I led them with cords of human kindness, with bands of love. I was to them like those who lift infants to their cheeks. I bent down to them and fed them.” Is the divine not describing itself by the attributes of motherhood?

It's time we returned to worship of both beauty and majesty, divine father and divine mother. And to the rhythm of push and pull, expand and contract. And to the joys of intimacy and separation in harmony with each other. To an understanding that justice and mercy are not in opposition, but fluidly intertwined.

We’re out of synch, all of us now, with each other and with ourselves, twitching to music we can’t hear. And it’s killing us.

Subscribe to this substack for free.

Check out my memoir, a collection of personal essays about living in the aftermath of childhood torture, with a feminist perspective on the society that enables the rape and pillage of children.

a little bit of god

a little bit of god is a memoir that spans 400 years, as the author tracks the origins of her life story to the birth of the European “Age of Reason.”

Oh my goodness, another woman who has been all over the religious map! You're right about Calvin—he's got his sticky fingers in many Protestant denominations. That "God-thinks-I'm-better-than-you" sort of arrogance is what justified so much colonization.

Your ending line is just beautiful: "We’re out of synch, all of us now, with each other and with ourselves, twitching to music we can’t hear. And it’s killing us."

There is no one monolithic “western culture.” Just as there as many forms of Islam—from Sufism to the Taliban enslaving women today—and many forms of African cultures, all geographic regions have given rise to manifold expressions of thinking and doing.

In fact, the European enlightenment is one of the rare moments in history since the dawn of agriculture when the idea that women have equal value to men was fully articulated and brought into the public sphere.

Enough with the unreliable generalizations in Substack writing. It does not help us to see the world fresh.