The Elder Activist

Why I Decided to Finish and Publish My Memoir

Way back when I was struggling to support myself as a 20 something-year-old who had already failed at one career, I got myself a part time job teaching English as a Second Language at a local community college. It seemed well within my intellectual abilities and perhaps not too stressful to bear.

It turns out it was stressful – I didn’t realize how terrified I was of people – but it was also exhilarating to serve the mature adults who had come to Canada for new lives and were juggling jobs, children and school. Under the influence of a fellow teacher, I pretty quickly ditched the available ESL texts to focus on using students’ life experiences as the center of my classroom work.

I would come up with a topic – scariest experience in life, a decision that changed my life -- and we would have a class discussion about it before they would write short personal essays. Then would come the workshops, in which they would critique each other’s writing (and find out a lot about each other). I found that students could be exceptionally engaged in learning when the learning centred on writing their own autobiographies in the miniature format of the personal essay and discussing them with classmates.

I had always written stuff – short stories, poems, lots of poems – so I naturally kept a diary of my journey into myself when I began therapy in my late thirties. By that time I had also moved to a different college where I was teaching remedial reading and writing skills. I used a lot of personal essays in those classes. So it was almost natural that I would transform my journal entries into short personal essays.

After a few years of digging into what I called a “wound” left by a childhood of sexual and physical abuse, I had enough essays for a collection. I prepared to send it off to book publishers. A few of my colleagues in the English department where I was teaching by then were kind enough to read the manuscript, and one of my colleagues who was a published author recommended my manuscript to her own publisher.

Their response was disturbing. They wrote to tell me they had already published one such book and that was enough. And they told me they received about a thousand such manuscripts each month. At about the same time the mostly male book reviewers had coined the mocking term “viclit” to categorize what was emerging as a new genre of literature.

I sent my manuscript to all of the Canadian and American publishers that had already published one memoir of a woman’s recovery from childhood abuse and met with the same response from all of them. One was enough; they didn’t want to become “known” for publishing such documents of the ramifications of cruelty to children inflicted by parents, caregivers and “friends of the family.”

A couple of the publishers were impressed with my manuscript, but it made no difference. So sorry, they said, we can’t take it on.

I tucked the manuscript and my disappointment away, but continued writing personal essays. Two were published by small literary magazines. One was awarded first place in a Federation of BC Writers’ competition. They now appear in the expanded book.

In the following years I developed a creative writing course on the personal essay and began teaching 22 students a year to write personal narratives. They wrote about difficult events and experiences: getting an abortion, entering prostitution, contracting a serious illness, starting rehab, dealing with death. I found I was teaching people the importance of personal stories to effect personal transformation, and to bring attention to social issues, and seeing again and again the power of the personal to affect other people.

All the essays were workshopped by students in the class and they achieved formidable skills, I thought, in giving tough criticism to the expression of a student’s life experience while avoiding judgementalism. These classes were the most intense of any that I taught, both sobering and exhilarating, and both I and the students gave much more time to them than we could afford.

They kept me inspired to write about my own evolving life of recovery, and I wrote essays on those “milestones” of western adult life – buying my first condo, then my first house, falling in love, falling out of love, fighting against and coming to terms with the politics and norms of my society. My responses to all those events were, of course, inflected with the long-term effects of childhood abuse. Everything I did was part of my recovery, and everything that I wrote was a coming to fuller understanding of the past’s effects on me.

My therapy, with or without the assistance of a therapist, continued, blossoming into a life of recovery, of “rebirth” experiences, as I saw that I was constantly regenerating, again and again being renewed after the processing of increasingly brutal memories.

It was becoming clear that my father, the primary abuser of my earliest childhood, was trafficking me into gangs of both men and women who shared their children and in the heightened dynamics of the group, escalated the abuse they inflicted.

Out in the world of the 1990s all hell was breaking loose as other adult survivors claimed similar memories. What was once taboo – revealing that fathers sometimes raped their children – had escalated into what was even more taboo – that neighbours might get together to brutalize children in rituals of torture. A backlash followed swiftly. A curtain of silence descended.

But behind that curtain a field of knowledge was growing, particularly how to identify and treat the extreme dissociation suffered by survivors. War survivors were diagnosed with a new psychiatric disorder they called post traumatic stress disorder, PTSD, which also fit adult survivors of sexual abuse and domestic torture. When possession of child pornography became a criminal offense in 1993, law enforcement could discover for itself what some adults would do to children.

New technology both enabled the spread of filmed child torture and revealed the extent of it to organizations mobilizing to fight against it.

The major distributor of porn worldwide, Pornhub, was located in Quebec where the Canadian government was content to let it take in billions of dollars for the filmed rape of minors and child sexual torture. And with the advent of the dark web, there is no longer any doubt that a disturbingly large percentage of men are involved in pedophile rings and group torture of children, in filming it and distributing it for profit, in live streaming it.

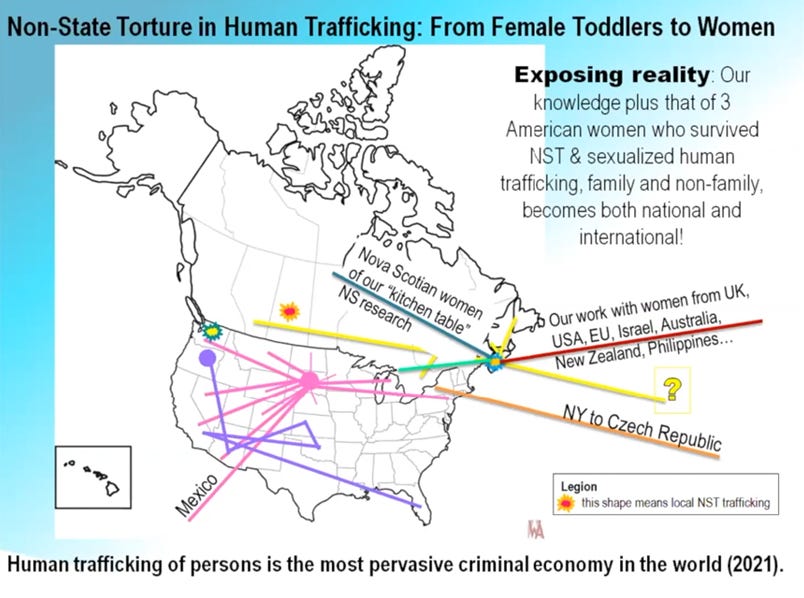

In the early aughts two Canadian nurses who had been helping victims of such abuse got together with American women to begin lobbying the United Nations Commission on the Status of Women (UNCSW) to get sanctions against what they were calling ritualized torture by non-state actors. They subsequently shortened this to Non-State Torture (NST) and have been speaking and lobbying ever since.

In 2007 they succeeded in having torture included in the UNCSW outcome document “as a form of violence against the girl child” (UN Commission on the Status of Women, 2007). Still, the Canadian government refuses to make NST a criminal offense. The most the perpetrators can be charged with is sexual assault against a minor. In 2021 the women, Jeanne Sarson and Linda MacDonald, launched their book, Women Unsilenced: Our Refusal to Let Torturer Traffickers Win, which is helping to raise awareness.

Here is a slide from a presentation they gave to an organization for domestic shelters in 2023.

I was motivated to compile all my essays, write some final thoughts, and publish the manuscript partly as a response to the work these women are doing to expose the crimes carried out against me and so many others. It is part of the activism on behalf of women and children that I’ve been engaged in since I retired.

Group ritualized torture of children is on the rise, as documented by the Canadian Centre for Child Protection. Changing cultural norms as a result of various social justice movements are being exploited by powerful predators who are increasingly claiming that children should be regarded as fully autonomous human beings capable to initiating and consenting to sexual contact with peers and with adults. To regard children as subject to the guidance and control of their parents is a violation of their human rights, they argue.

If adults, if mothers, are prevented from safeguarding their children, I think we will descend quickly into a nightmare world of unchecked depravity and brutality.

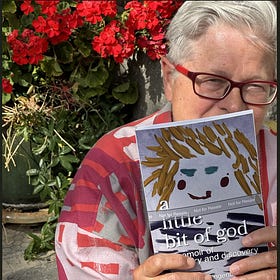

My book is a testimony of abuse, but more than that, it is a testimony of the power of healing. It documents the possibility that the self-loathing, shame and guilt of survivors can be transformed into righteous anger, which can fire social change. I offer it as hope to other survivors. We can achieve peace, and even forgiveness as we demand these crimes be recognized.

Social denial of the worst cruelties humans can inflict is strong. Most of us prefer to think that our fellow citizens, our neighbours, are basically decent people and when crimes against women and children are reported, we most often avert our eyes and ears. And so such crimes metastasize. We can’t fight against what we refuse to see or name.

While my book is for sale as both an ebook and a paperback on Amazon, my plan is to disseminate it through little free libraries. I’ve already distributed dozens to the little libraries in my west coast city and hope to recruit other women to distribute them in cities across the country. I also did a little guerilla librarianship, putting the book on the new releases shelf at my local library.

For me, the healing continues. Publishing the book led to multiple repeated flashbacks, which gave me insight into how the perpetrators of my abuse taught me never to tell. By clicking “publish” on the Amazon KDP website, I told the entire world.

Is the world willing to hear?

If you’d like to buy the book, or just read/listen to a sample, click on the link below.

If you’re in Canada and might be persuaded to join a crew of amateur book distributors, get in touch!

Don’t be alarmed that the author’s name is a little different then the one I use here. We are the same person.

This substack is always free.

From Death to Life

Sometimes a spiritual journey requires a descent into hell. So it has been for me. And yet . . .then I have been to hell twice. The first time in real experience, the second in remembrance. Maybe that's always how it has been. Maybe those who know of the "valley of the shadow of death" have been there, like me, to pick up their lost inner selves, the ch…

https://substack.com/@kalikarma1/note/c-182787631?r=6oi3ss